4 Quick Tips to Adapt Your Screenplay into a Graphic Novel Script

Last week, I got an email from a reader who “had experience writing film scripts…and would like to convert a current film script to graphic novel format.” So I created a list of four tips for him to keep in mind during his adaptation, and I figured there might be others who could benefit from the same tips. Enjoy!

Last week, I got an email from a reader who “had experience writing film scripts…and would like to convert a current film script to graphic novel format.” So I created a list of four tips for him to keep in mind during his adaptation, and I figured there might be others who could benefit from the same tips. Enjoy!

Note: Before adapting your screenplay to a comic script, know that many artists in the industry work from screenplay format, and if you hire a good comics artist, they can adapt the screenplay into static images and save you the trouble of doing the adaptation yourself. The tradeoff is relying on the artist to do more of the work, which will require more payment and trust in them to make decisions as your collaborator.

That being said, if you’re still keen to do the adaptation yourself, then hopefully the tips below are helpful.

* * *

1. Describe One Action at a Time

If you’ve read my script formatting post, Graphic Novel Script Format, then you know that there is no standard script format for writing graphic novels, but there are two main styles: Full Script and Marvel Method. A screenplay is like an unfinished Full Script, so let’s assume you’re adapting your screenplay into a Full Script.

The key difference between a screenplay and a graphic novel script is screenplays describe moving pictures, while comics scripts describe static pictures.

So, as you go through your adaptation, be mindful to describe ONE static moment at a time.

Example: As it is written, what does the following look like?

He picks up the phone.

MAN: Hello?

It looks wrong because picking up the phone and speaking into the receiver are TWO actions, not ONE.

It should be written as follows:

He picks up the phone.

He holds the phone to his ear, upside down, and speaks into the wrong end.

MAN: Hello?

(Please excuse how outdated this joke is. 🙂 )

(Please excuse how outdated this joke is. 🙂 )

When there are two or more actions in each moment, the artist will have to pick between them or add unnecessary panels to be true to your script.

A simple trick is to think of each comics panel like a still photograph. Like comics, photographs can capture only ONE visual moment at a time. There are technological tricks to imply movement (blur filters in Photoshop, etc.), but try not to use them. It’s better if each figure is frozen in time.

Separating every action from the other will make you discern which actions you need to get the story across, and clarify exactly what you want the artist to draw.

Exception: I can already hear the comic purists yelling, “Nah uh! What about the polyptych, huh?!”

Alright, alright! I was trying to keep it simple, but it’s true that an element of comics storytelling is the polyptych—as Scott McCloud defines it in Understanding Comics, “where a moving figure or figures is imposed over a continuous background.”

Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud

Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud

So, technically, many things could happen within a single panel. But I opted not to emphasize this storytelling tool because many of my screenwriting clients have used it as a crutch to doing the more difficult work of separating and pairing actions down. They try to cram in as much movement as they can, when it’s often not needed and the result is a mess.

If you’re new to writing comics, I’d highly highly highly suggest letting the artist suggest a panel like in the examples during the collaborations. Otherwise, assume you need to separate every action from the other.

2. Be Brief (<25 Words per Panel)

Most readers pick which graphic novels they want to read based on the quality of the visuals—much like we judge a book by its cover (even though we’re not supposed to). So, give the artist as much room as you can.

One way you can do that is to aim for fewer than 25 words of dialogue per panel. More words than that and the artist will have very little room to do the drawing.

Example: The panel below has 16 words and already it’s starting to get crowded.

Li’l Nauts in Hypertot at the Bat, written by Tim Stout, illustrated by Jason Week.

Li’l Nauts in Hypertot at the Bat, written by Tim Stout, illustrated by Jason Week.

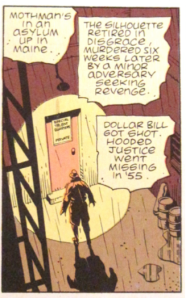

Example: This panel has 31 words, and as you can see, the artist, Dave Gibbons, has had to make the character small in the panel to accommodate all the words.

Watchmen, written by Alan Moore, illustrated by Dave Gibbons.

Watchmen, written by Alan Moore, illustrated by Dave Gibbons.

I don’t mean to say you can’t have more than 25 words per panel, but be aware that the more words you have, the more difficult it will be for the artist to provide good and interesting visuals. And graphic novel readers are hungry for good visuals.

Visual space is your most valuable resource, so be brief.

This goes for the length of your script, too. Comics are really time-consuming and very labor intensive for the artist. Most graphic novels take 3–4 years to produce AFTER the publisher has purchased the script—usually because there are just so many drawings. A 100-page comics script is probably about 500 drawings.

The artist will have to do sketches, revisions, implement editorial notes, draw again, more notes, ink, more notes, lettering, more notes, color, etc. So the more panels you have, the longer it will take to produce. The longer it will take to produce, the more time an artist and/or publisher must be willing to commit to the project. So, make it easy for them to say yes.

Cut as many pages as you can to still tell the story you want to tell. Cut as many actions as you can to still get the point across. Cut as many lines of dialogue as you can. Cut as many words within that line of dialogue as you can. Be brief.

Edit down to only the things that MUST happen.

3. Describe ONLY What a Reader Can SEE.

Screenwriters typically get this lesson faster than novelists, but when writers start writing for graphic novels, they often over-describe. This is normal. They are not used to describing something for an artist, so they don’t yet know what is too little or too much information to get the drawing juuuust right. So, they often do too much, just in case.

Descriptions need to be ONLY what the reader can SEE.

Comics are a visual medium. If the reader can’t see something, it doesn’t actually exist.

Example: A boy lies in bed, staring up at the ceiling. He is angry because he thinks his mother is being unfair. It’s not his fault that the ceiling collapsed!

All I’ve SEEN in this example is a boy lying in bed, staring up at the ceiling. And he’s probably scowling, or something. The rest is a novelization of his feelings and backstory, which either need to be adapted to some kind of visual, or cut from the script. If you can’t see it, cut it.

It’s true that the artist will need to understand the nuances of a moment, but artists are smart and spelling everything out for them will feel disrespectful. Let the artist ask for clarification if something doesn’t make sense to them.

4. Rely on Action, Reaction and Gestures, Not Facial Expressions

Quite often, writers will use facial expressions as a crutch to depict the emotion of a moment, visually.

Fortunately/Unfortunately, in comics, the drawing of a face is a simplistic abstraction and/or an exaggeration, so emotions need to be simplistic abstractions and/or exaggerations.

Fortunately/Unfortunately, in comics, the drawing of a face is a simplistic abstraction and/or an exaggeration, so emotions need to be simplistic abstractions and/or exaggerations.

Simple emotions have an easier time being drawn and they do just as good a job as complex emotions because the reader will infer what a “frown” means within the context of the drama.

Besides, complex emotions behind a still face do not lead to a complex or rich character. Character is shown through actions and reactions to conflict. Stick to that. Otherwise, the artist will have to simplify the expressions for you.

Action, reaction, and gestures are more reliable tools in comics than facial expressions.

* * *

And there you go. If you stick to these 4 simple tips, then you’ll be ahead of 80% of the comics scripts I see from screenwriters.

Best of luck on your adaptation!

I love these articles, Tim. However, I still have some questions. In my youth, I frequently read novels with illustrations, as well as comic books. My project is more of the latter, as I want the illustrations to accompany text in many different languages. Not to mention, my project is dialog-intensive. For example, if I have a “dinner scene” I may want one drawing to accompany a page or more of dialog. In other places, I may need several panels to describe the complicated actions of a system, such as someone boarding a helicopter just as the engine starts and the blades begin to turn. Is this done? Even if this is done, have any such illustrated novels been successful?

To be specific, last summer I wrote a 22 page science fiction romantic comedy that I have expanded into both a 90 page screenplay and a 92 page shooting script. I plan the illustrations to act as a storyboard for a feature film, much as the old Dell movie series of the 1950s and early 60s. http://s302.photobucket.com/user/uncacreepy/media/ebay1/master-of-the-world.jpg.html

I would also like to know if anyone has designed such an illustrated novel for some of the color e-book readers that will also play MP3s, as I use music extensively to both advance the plot and shade characterizations. My goal is to not only penetrate the graphic novel market but also to produce a promotional video for investors who can then almost perfectly visualize how a completed film will look. I feel strongly that this is the future of film production.

I would appreciate any comments or cautions you might wish to offer. Thank you.

Thanks for the comment, Robert.

My project is dialog-intensive. For example, if I have a “dinner scene” I may want one drawing to accompany a page or more of dialog.

I don’t recommend this, but it’s your story.

In other places, I may need several panels to describe the complicated actions of a system…. Is this done? Even if this is done, have any such illustrated novels been successful?

This is done in comics all the time. Find a graphic novel or comic that does it well and emulate it.

To be specific, last summer I wrote a 22 page science fiction romantic comedy that I have expanded into both a 90 page screenplay and a 92 page shooting script. I plan the illustrations to act as a storyboard for a feature film.

If you plan to do all this to sell the screenplay, don’t bother. Just try to sell the screenplay. Graphic novels take a long time to make and don’t guarantee a better chance at getting a movie made.

I would also like to know if anyone has designed such an illustrated novel for some of the color e-book readers that will also play MP3s.

I haven’t seen it, but if you find a way to make that work, that could be cool.

Hi, Tim. I’m a novelist, not a graphic novelist. I’m working on the third book in a sci fi trilogy and readers keep telling me I should make it a comic book series. I found this post while researching options for doing so. Is it best for an author to write the screenplay, or find someone to read their novel and write it for them? If the latter, can you suggest steps or a post you have outlining steps, for the best method for a novelist to add her novels to the comic book world? Thanks!